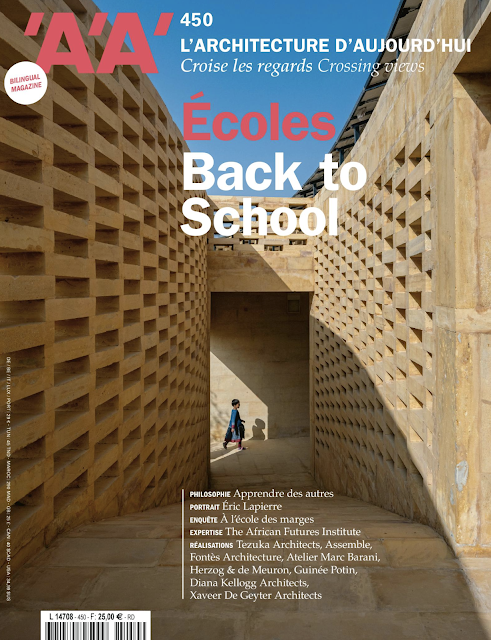

Lesley Lokko and the African Futures Institute, L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, Sep. 2022.

A Laboratory for Contemporary Spatial Identity: Lesley Lokko and the African Futures Institute

Scottish-Ghanaian author and educator Lesley Lokko founded the African Futures Institute last year in Accra, Ghana as a way to position Africa and the diaspora at the center of a transformative vision of the relationships between identity, the environment, social justice, and architecture. A widely published novelist and architectural educator, Lokko founded the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg in 2014. In 2019, she became dean at the City College of New York’s Spitzer School of Architecture but left the following year in what she described as a profound act of self-preservation and returned to Ghana. This year, the Venice Architecture Biennale selected her to curate its 2023 edition, The Laboratory of the Future.

AA: What is the project of the African Futures Institute?

The best way I can describe it is to say that in 2014, I started a school of architecture in Johannesburg, the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA). The GSA was a really interesting experiment. It came on the back of student protests about decolonization and access to tertiary education. Taking a curriculum that had originally been developed at the Architectural Association in London and transplanting it to South Africa was actually fairly revolutionary, and the students responded to the curriculum in really interesting ways.

The plan was to try and do something similar in New York, which didn’t work out. When I left Spitzer, I thought, if I don’t go back to home now—back to Ghana, to West Africa—I probably will never do it. The idea was to set up an institute very much like the GSA. The mandate is really simple: it’s to provide world-class architectural education here on the continent, but also to take the more experimental, radical space that Africa offers to think about architectural education differently, not just for Africa, but globally as well.

AA: Do you have some intuitions about the role of architecture in imagining identity on the African continent and what the process might yield?

For me architecture has always been very narrative driven. The physical artifact, the building, is always trying to tell some kind of story. Particularly in—let’s call it the Global North, it’s assumed that story is a universal one. But actually it’s quite culturally specific. If you come from locations outside of that canon, you don’t see yourself, your cultural values, your beliefs reflected in the environment. You don’t see the school as a space where you can explore how to translate different narratives into form.

The school really ought to be the protected space where you can grapple with these really difficult questions of identity, of language, of history, of occupation, of settlement. Africa is the youngest continent; the average age is 20. There’s an incredible energy here at the moment, with very little infrastructure to be a platform or a catalyst for that energy. What I’m seeing in the creative industries—music, fashion, film, photography, art—is almost an explosion of a pent up desire to say something, and architecture has been very lax in taking up that challenge. Those of us who are in our late 50s/ early 60s have the possibility to put those structures in place, which is what the AFI is.

AA: In Issa Diabaté’s lecture last year at AFI, he talks about passive techniques for mediating climate at a domestic and institution scale. It’s an incredibly hopeful vision from a purely technical point of view to moderate climate on a human scale through architecture.

The power of the imagination to suggest ways of thinking, working, seeing, for me, is the real draw in education. The university’s draw is a place where you construct new knowledge. There’s a tendency in architectural education to think of it as training. You perfect something that’s already there. On this continent, students understand that somehow architecture has failed them. They’re not afraid to go beyond it. There’s a curiosity about other disciplines and a willingness to work across fields that I don’t encounter in the Global North.

The relationship between climate and landscape, for example, or between landscape and narrative, or between narrative and emotion, those distinctions here are quite blurred, and it produces really interesting, thought-provoking work. And it’s too early to say what the translation into architectural form will look like—we’re still in the process of figuring that out—but if you think of architecture as being about the building of knowledge almost as much as the building of buildings, there’s an appetite here to build new knowledge that for me is unparalleled.

AA: Olalekum Jeyifous, who lectured at AFI recently, also does work along these lines, in which he’s scripting an alternative set of conditions through which a space is created.

Absolutely. Jeyifous is a good example. I think, if there were 100 more like him, we would have 100 times the power of that imaginative courage. Lek would describe himself as somewhere between a filmmaker, an artist, an architect, and an activist. That boldness in slipping in between categories is really compelling right now. A school like the AFI should be a place that incubates that confidence.

AA: Can you talk about the AFI’s ambition to engage architecture in rethinking the relationships among African governments and between them and international powers?

I remember distinctly as a student that my culture—Africa, blackness—had very little to offer architecture. I felt like a supplicant coming to this very well-established discipline with a few concerns and ideas of my own, almost begging for an audience. Architecture had no use for anything African, anything black, anything other. It was seen as an affront to architecture. Those of us with those sorts of concerns were always agitating at its edges. The feeling that I got then was that we were lacking—by we, I mean the diaspora, otherness—and that we were too chaotic, too disorganized, too corrupt, too inferior, and that we had nothing to give architecture.

After 30 years, I swear I have come full circle and I understand now that it’s actually architecture that’s lacking. It’s not able to deal with the complexity and the contradictions that a context like Africa throws up. If you think about hybrid or diasporic identities that are multiple, made in more than one location, people who speak more than one language or have more than one home, fundamentally architecture is about the opposite of that. It’s about grounding something, making something solid and in place, and here we’re talking about cultures that are very much out of place.

The next five or ten years are going to be very exciting ones for architecture as a discipline because climate change has suddenly forced the issues of climate and climate justice onto the table. In the same way that Black Lives Matter put questions of race and identity back on the table, architecture, finally, after so long, has an opportunity to respond. These questions of decolonization are a gift to the canon. They enrich it. They don’t destabilize it or diminish it.

AA: As you were saying, you can see it in these Afrofuturist fashion gestures and in art and visual culture. We’re already living in a future that hasn’t quite appreciated the changes already in place. Our selves are partly merged with machines in many ways, and we’re multiple in terms of cultural exposure in ways that people have probably never been, ever.

One hundred percent. Even though the AFI curriculum focuses especially on Africa, we are all African. The conditions that operate here, conditions of translation, of movement, the African diaspora, the fact that the official languages are English, French, and Portuguese, but everyone speaks another language behind closed doors. All of those questions many people around the world resonate with, it’s not just Africans. If you think about what we’re trying to do with architecture as an analogy for what’s happening to many, many people—in terms of sexuality, identity, location—it’s all here. My hope is that by focusing very specifically on a place, you’re able to tell a story that resonates far beyond these borders and gives some kind of—maybe hope is too strong a word—it gives a push, an impetus to students and practitioners and activists who have the same questions.

One of the reasons why it was possible to implement something so different in South Africa was precisely because the level of anger that was brewing in the student population anyway. I thought after George Floyd and after the pandemic that there would be similar levels of anger in the Global North, but that anger has been translated into a kind of fear, and fear for me is often not a productive place to start from. It’s defensive. It’s insular. It’s often quite reactionary. Anger, by definition, is outward facing. It’s about change. I’m not saying that students have to be angry, but in a climate where anger is palpable, you can get an incredible amount done. In a climate where people are fearful, my experience is that you get almost nothing done. The amazing thing about educational projects is that you plant a seed and suddenly it sprouts somewhere. The group of young students in Johannesburg who became tutors and young practitioners did things you could not possibly have predicted.

AA: Is there a resonance between the African Futures Institute and plans for the Venice Architecture Biennale?

It’s an unusual curatorial position because on one level, I am the African Futures Institute: the separation between it and myself is very blurred. It’s unusual that something so young and fresh—the AFI is a year old—would have such an opportunity for such a global presence. On the other hand, I’m a fiction writer as well as an educator, and it very much is the same story that I’ve been talking about for the last 30 years. It feels almost surreal to have thought about my work as very marginal, and suddenly, after the pandemic, George Floyd, and all of the upheavals of the last two years, to find that it’s of interest to a wider audience. The college project of the Biennale could be very interesting, because for the first time we will have an educational project that runs alongside the Biennale.

AA: I love the fact that you’re emphasizing a humanities and social science education.

I inherited those terms like humanities, social sciences, sciences, and physical sciences, and for a long time I thought of them as sacrosanct. But when you come here to the African continent and you’re confronted with a knowledge system that’s very different, it makes me question all of those assumptions about the separation of knowledge. For me life—as far as I understand it—is narrative driven, it’s about the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves.